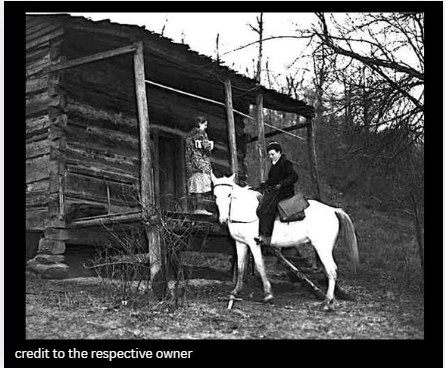

In the summer of 1938, in a remote corner of Appalachia, a lone librarian saddled her horse at dawn and set off down an overgrown trail. Her saddlebags were heavy—not with mail, not with supplies—but with books: dog-eared copies, new editions, and volumes of hope. This was part of the Pack Horse Library Project, an initiative born of desperation and idealism during the Great Depression. Across rugged terrain, through fog, rain, snow, and mud, these “book women” carried stories to people who otherwise would have no access to them.

The Birth of a Horse-Bound Library

During the 1930s, much of rural America was struggling. Roads were sparse, isolated communities were cut off by hills and hollows, and educational resources were scarce. In response, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) instituted the Pack Horse Library Project, a bold experiment to bring books to the underserved. In counties across Kentucky, librarians were hired—many of them women—and asked to ride out into remote areas, often following old trails, climbing ridgelines, and braving unpredictable conditions so that readers in mountain hollows could have books.

One of those librarians, driven by quiet conviction, became a figure of silent courage. She didn’t ride for accolades or a large paycheck (in fact, she earned only $28 a month). She rode because she believed in something greater: that knowledge, fairy tales, histories, poems, and stories have the power to transform lives—even when delivered via horseback.

A Week’s Ride, a Traveler’s Resolve

Some weeks, the journey spanned 60 to 100 miles. Imagine leaving before dawn, riding through low clouds, crossing creeks and gullies, pausing to catch your breath, and then pushing on. The path was seldom easy. In winter, snow and ice made the journey treacherous. In rainy spells, trails turned to muck, streams swelled, and horses slipped. In summer, fog blanketed ridges, hiding the way. But for every mile she traversed, for every book she carried, there was someone waiting at the other end: a child craving a bedtime story, a teacher needing a reference text, a laborer hoping for a brief escape in a tale.

She packed a mix of titles—some old, some new, some lighthearted fiction, others serious history or poetry. Every delivery was a small gift. Sometimes she left books in cabins, sometimes met readers on a hilltop, sometimes stayed the night in a family’s home before riding on the next morning.

More Than Books: Bridges to Connection

The work was never merely logistical. In those hollowed-out spaces, isolated by geography and poverty, she became a bridge to the larger world. She arrived with a book in hand—and conversation. People would ask about the outside, about what was happening in distant cities, about news, about dreams. She’d become a welcome visitor, a link to ideas beyond the mountain folds.

Children, many of whom never had a book of their own, looked forward to her visits. Families read aloud by firelight. In one small cabin, a mother sewed garments by daylight and read worn copies by lamp at night. In another, an elderly man, whose schooling had ended early, pored over a short story he’d never before encountered. In a place where radios were rare and newspapers came infrequently, these borrowed books became lifelines to imagination.

The True Cost of Delivery—and Why It Was Worth It

Her pay—$28 a month—barely covered necessities. Some roads she traversed were no more than animal paths. Supplies were minimal. She carried a lantern, a few dry goods, and sometimes a small lunch; often she relied on the kindness of residents to share a meal or offer a place to stay. Horses had to be cared for, paths repaired, trails memorized. Illness or injury on the road could become life-threatening when medical help was distant.

And yet, she persisted. Because in every remote cabin she entered, in every eager child’s eyes, lay the proof of her mission’s worth. The excitement when a family got a fresh novel. The hush when someone read aloud for the first time. The gratitude uttered by parents who had never thought their children might read. These were quiet but profound victories.

Legacy Beyond the Mountains

By the end of the Pack Horse Library era, thousands of books had made their way into the hands of rural Kentuckians who would otherwise have gone without. Entire communities—once barren in educational resources—gained access to stories, facts, dreams, language, and hope. The project eventually wound down, but its impact lingered: it planted seeds of literacy, of possibility, of the belief that books matter—even when the path to deliver them is steep.

Today, we might take for granted the convenience of digital libraries or mobile phone internet access. But back then, knowledge was literal freight, to be carried on a horse’s back. The “book women” remind us of a simple truth: where there is a will to learn, there are individuals willing to risk everything to bring knowledge.

So next time you pick up a book, remember her ride through the hills: the miles traveled, the cold rain soaking her clothes, the flickering of a lantern in a cabin, and the moment a reader cracked open a new page. Those journeys weren’t just about books—they were about dignity, connection, and belief in human potential. And even today, their legacy asks us: When opportunity is distant, who will ride to deliver it?